Maps of the Antique

Mediterranean Sea

The Etruscans The Etruscans

Overview Overview

Some dates Some dates

Archaeological sites Archaeological sites

Museums Museums

Etruscan Art Etruscan Art

Coinage Coinage

Language and Writing Language and Writing

|

ETRUSCAN ART

This page is partly based on educational material collected by our partner "Mysterious Etruscans",

with his kind authorization.

All rights reserved.

Jewellery - Frescoes - Sculpture - Pottery - Bronzes - Mirrors

In all studies of Etruscan art, it should be remembered that a large proportion of Etruscan art did not survive up until the present day. We read of the Roman destruction of Volsinii and the destruction of 2000 Etruscan bronzes which were melted down to produce bronze coins. As a result of this, we have a somewhat skewed perception of Etruscan art, in that most of the art that survives today is funerary art, and we form totally wrong impressions about the Etruscans as a result.

From excavations at Murlo, Roselle and other city sites, it is apparent that art was a normal part of Etruscan life. In Murlo, a seventh century Etruscan villa has been unearthed. Reconstructions show large painted terracotta panels adorned the entrances. Necropolis art in the form of polychrome reliefs and frescoes hint that the Etruscans used colour to great advantage even from the earliest times. Although painted tombs are among the most famous, it should be remembered that these represent a minority, and that only the aristocratic families could afford such luxuries as tomb frescoes.

The image left shows part of the antefix from the temple of Juno Sospita, Lanuvium (6th - 5th Century BCE). This terracotta depicts a maenad, Many similar examples have been found, in many cases with traces of the original polychrome decoration. The characteristic smile is shared by many statues of the contemporaneous Greek Archaic period.

Etruscan Art has been said by some 19th and even 20th Century writers to be somehow inferior, although this was usually by erroneous comparison to the Greek mathematical ideals of beauty. Nowadays we can appreciate Etruscan Art much more readily, since Etruscan Artists seem to capture the feeling and the essence of so many of their subjects so much better than for example art of the highly stylised Classical period. The image left shows part of the antefix from the temple of Juno Sospita, Lanuvium (6th - 5th Century BCE). This terracotta depicts a maenad, Many similar examples have been found, in many cases with traces of the original polychrome decoration. The characteristic smile is shared by many statues of the contemporaneous Greek Archaic period.

Etruscan Art has been said by some 19th and even 20th Century writers to be somehow inferior, although this was usually by erroneous comparison to the Greek mathematical ideals of beauty. Nowadays we can appreciate Etruscan Art much more readily, since Etruscan Artists seem to capture the feeling and the essence of so many of their subjects so much better than for example art of the highly stylised Classical period.

The styles of Etruscan Art vary considerably between the individual Etruscan cities, and there was also significant variation on style depending on the period - so much so that we can date Etruscan art works in many cases by comparison with other examples.

The interest in Etruscan Art grew during the renaissance, at which time the extant Etruscan art had considerable stylistic influences on the emerging artists of the renaissance, many of whom lived in former Etruscan cities where such art was plentiful.

By the nineteenth century, Etruscan art had grown to a passion, and the "excavation" of Etruscan tombs to meet growing demands increased. An example of this is the brother of Napolean, who owned land near Canino, which included the Etruscan necropolis of Vulci. These "resources" he exploited to great effect, destroying many pieces of Etruscan art in the process, and covering in the tombs with soil afterwards. As a result of this and many other examples, we now have thousands of pieces of Etruscan Art whose provenance is unknown, and which are still in private collections , or have been donated to museums in Europe and the United States.

The Art of The Etruscan Gold-Smith

Etruscan gold work was arguably unrivaled in the Mediterranean during the first millennium BCE. A considerable selection of Gold jewellery was found in the Regolini Galassi tomb, which Etruscan gold work was arguably unrivaled in the Mediterranean during the first millennium BCE. A considerable selection of Gold jewellery was found in the Regolini Galassi tomb, which  was discovered in the 19th Century, surprisingly with little evidence of looting. Looting was all too common in Ancient days, and was even encouraged officially by Alaric the Goth when his armies overran Rome in the early 5th Century AD. was discovered in the 19th Century, surprisingly with little evidence of looting. Looting was all too common in Ancient days, and was even encouraged officially by Alaric the Goth when his armies overran Rome in the early 5th Century AD.

This magnificent gold fibula was taken from the Regolini- Galassi Tomb, Cerveteri (Caere) and dates back to the 7th Century BCE. This is one of the finest examples of Etruscan goldsmith's art. This illustration does not do justice in revealing the fine work that went into such a piece. The precise technique of granulation was for a long time a forgotten art, and it was only rediscovered in the 20th Century by E Treskow (a fibula is a kind of large ornamental safety pin used to fasten a robe). The Fibula on the left is another illustration of the art of the Rasenna goldsmiths.

More about this subject : see our partnerís page

Etruscan Frescos

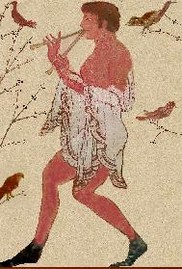

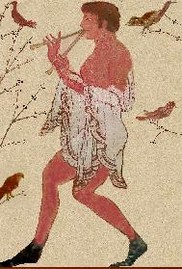

Above Left: From the tomb of the Lionesses, Tarquinia. Above Right: From the tomb of the Triclinium, Tarquinia.

Both pictures illustrate the ubiquitous Etruscan joie de vivre. These are very typical of so many Etruscan Frescoes which depicted figures vibrant with life, often dancing or playing musical instruments. They painted birds or animals on many of these intermingled with the human figures, who usually looked strong and healthy and full of the joy of life. The little birds and other figures from nature somehow do not seem out of place or look like mere decorations, but lended a natural harmony to the finished work. More about this subject : see our partnerís page

Sculpture

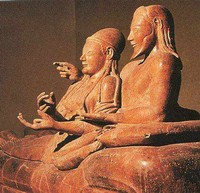

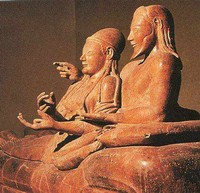

The sculpture on the right (actually a hollow cinerary urn) comes from the Banditaccia necropolis, Cerveteri, and is known as the Sarcophagus dei Sposi. It is currently exhibited in the Villa Giulia museum in Rome. The terra cotta sarcophagus lid with figures of a man and woman, presumably his wife reclining on a triclinium or dining couch presumably eating a meal or having a quiet moment after supper The sculpture on the right (actually a hollow cinerary urn) comes from the Banditaccia necropolis, Cerveteri, and is known as the Sarcophagus dei Sposi. It is currently exhibited in the Villa Giulia museum in Rome. The terra cotta sarcophagus lid with figures of a man and woman, presumably his wife reclining on a triclinium or dining couch presumably eating a meal or having a quiet moment after supper

Both figures are propped up on their left elbow with the man close behind the woman. Both faces share a secret, tender smile. A very similar sarcophagus to this was also found in Cerveteri. They are believed to be by the same artist and date to 520 - 530 B.C. A very similar sarcophagus to this was also found in Cerveteri. They are believed to be by the same artist and date to 520 - 530 B.C. A very similar sarcophagus to this was also found in Cerveteri. They are believed to be by the same artist and date to 520 - 530 B.C.

The Greeks and later the Romans had some very pointed ideas about the Etruscans. Theopompus of Chios, a Greek historian who lived in the Fourth century BCE wrote of the morality of the Etruscans "...Further they dine , not with their own husbands, but with any men who happen to be present, and they pledge with wine any whom they wish. They also drink excessively and are very good looking. The Etruscans rear all the babies that are born, not knowing who the father is in any single case.....".

More about this subject : see our partnerís page

Etruscan Pottery and Ceramics

Etruscan pottery and ceramics adopted many different styles through the ages, sometimes faithfully copied from Greek or Middle Eastern models, but sometimes showing great originality that makes them readily identifiable. This variation in style more or less closely echoes developments in trade relations of the region.

The techniques themselves slowly evolved over many years: the first vases were made from clay of alluvial origin from a river or stream. By the seventh century they had learned to refine the basic clay, also called "raw clayĒ. This finer material was baked at 900 įC, and could produce much more valuable objects, which were thrown on a potter's wheel. The decorations were engraved or embossed.

During the Villanovan Period, the deceased were cremated, and the ashes placed in biconical clay urns. In later years, both burials and incinerations were common, and the sarcophagi were decorated with recumbent figures or took the form of a triclinium (banquet) beds, representative of the deceased with features reminiscent of archaic Greek statues.

The production of funerary urns, followed by black pottery gave birth to the Bucchero Nero, which was practiced up to the sixth century BC. The walls, which were initially thick, gradually became thinner, reaching their ultimate quality during the seventh century. Bucchero nero consists of a clay which is tinted black or sometimes gray, using a reduction process similar to metallurgical techniques. After polishing to produce a metallic sheen, it is often decorated with figures that are engraved, modelled in relief or carved. Among the many shapes obtained, the chalice, the high-handled kantharos and the amphora with two handles and bearing incised drawings are particularly typical. They aim to imitate bronze, which is much more expensive.

The production of funerary urns, followed by black pottery gave birth to the Bucchero Nero, which was practiced up to the sixth century BC. The walls, which were initially thick, gradually became thinner, reaching their ultimate quality during the seventh century. Bucchero nero consists of a clay which is tinted black or sometimes gray, using a reduction process similar to metallurgical techniques. After polishing to produce a metallic sheen, it is often decorated with figures that are engraved, modelled in relief or carved. Among the many shapes obtained, the chalice, the high-handled kantharos and the amphora with two handles and bearing incised drawings are particularly typical. They aim to imitate bronze, which is much more expensive.

Throughout the Etruscan period, we also find unglazed funerary or votives ceramics without any paintings, but decorated with engraved figures or figures modelled in relief before the clay had hardened. Their shape sometimes recalled everyday objects such as stoves, ovens and containers. The patterns include human figures, monsters borrowed from eastern Asia, and geometrical drawings. In Chiusi, in Volterra, Vulci, the drawings are rather in relief, whereas they are more often hollow in Veies.

Throughout the Etruscan period, we also find unglazed funerary or votives ceramics without any paintings, but decorated with engraved figures or figures modelled in relief before the clay had hardened. Their shape sometimes recalled everyday objects such as stoves, ovens and containers. The patterns include human figures, monsters borrowed from eastern Asia, and geometrical drawings. In Chiusi, in Volterra, Vulci, the drawings are rather in relief, whereas they are more often hollow in Veies.

In the 7th century B.C., as a result of exchanges with Mediterranean civilizations, ceramics known as etrusco-corinthian or italo-corinthian These imitate the Corinthian, and particularly proto-Corinthian ceramics, and fairly soon reached a quality almost equal to their models, but at the end of the century, the Etruscan workshops deviated from Corinthian models and adopted more original decorations and forms, closer to those which appear in Greece: oenochoes, olpes, then flat-bottomed alabasters, double-bodied aryballoi and various kinds of kylixes and dishes.

Between around 600 and 480 B.C., the commercial traffic led to a rise of new artistic methods. Painting obtained a decorative statute and are used on vases and frescos. Ceramics became very close to the Greek production, adopting the techniques of black figures, then of red figures. They also adopted original types (dolphins, animals) or characteristic patterns (Genucilia type). For a long time, Cumea and Nola produced vases with decoration inspired directly by the Greek schools.

Finally, starting around the 3rd century B.C. and even under the Roman period and the Christian era, the potters from Arezzo were also in great vogue. They generally used a terracotta of fine quality that was of unusually consistent quality, decorated with ornaments in relief and then glazed. This led in the 1st century B.C. to the sigillated earthware, which was imitated even in Gaul and Africa.

More about this subject : see our partnerís page

Bronzeware

During ancient times, the Etruscans were undisputed masters of the art of bronze sculpture, and were praised for this art by writers Greek and Roman alike. Athenaeus in his "Symposium" quotes  a poem by Critias in saying "Etruscan cup of beaten gold is king, and any bronze whatever that adorns the house for any purpose". Again from Athenaeus, a character in a play by Pherecrates is quoted as saying "The lamp stand was Tyrrhenian... for manifold were the crafts among the Etruscans, since they were skilled and loving workmen". Vitruvius in his famous work on Architecture refers to the superlative gilded bronze statues of the Etruscans, and Pliny the Elder writes "There are also Etruscan Statues dispersed in various parts of the world, which beyond any doubt were made in Etruria". a poem by Critias in saying "Etruscan cup of beaten gold is king, and any bronze whatever that adorns the house for any purpose". Again from Athenaeus, a character in a play by Pherecrates is quoted as saying "The lamp stand was Tyrrhenian... for manifold were the crafts among the Etruscans, since they were skilled and loving workmen". Vitruvius in his famous work on Architecture refers to the superlative gilded bronze statues of the Etruscans, and Pliny the Elder writes "There are also Etruscan Statues dispersed in various parts of the world, which beyond any doubt were made in Etruria".

Above: The Chimera of Arezzo - A mythological creature with the body of a lion, two heads (of a lion and a goat), and a serpent-like tail

Even today we have some magnificent examples of Etruscan bronze work in the Capitoline she-wolf (Romulus and Remus were added in the 15th Century). This is the Lupa, which the symbol of Rome even to this day. In Arezzo, another city symbol is the bronze Chimera, bursting with life, which can be seen in the local museum.

The names of the masters who made these sculptures are unknown, however what remains today is a sad remnant of the enormous treasury of Etruria, the El Dorado of the Ancient World.

This was a treasury not only in terms of monetary worth, but in terms of the incalculable artistic value, most of which is now lost.We read in Titus Livius that when the consul M Fulvius Flaccus overpowered the city of Volsinii, they despoiled it of all its precious treasures, its votive offerings and all other gifts. A long line of wagons packed with the plunder, including 2000 bronze statues set off for Rome, only to be melted down to be used to made Roman coins (aes grave) of bronze to assist with the war effort against Carthage. Metrodorus of Scepsis is reported (Pliny The Elder) to have reproached the Romans for plundering the city just for the sake of two thousand statues.

One of the most famous bronze working centres was the city of Vulci. Even into Roman days, the city remained an important centre for bronze ware, and drinking vessels, tripods with feet shaped like lions paws, and incense burners with dancers and Sileni were among the artworks emanating from that city.

During the peak of the Roman Empire, such cities as Clusium and Arretium were still producing excellent bronze ware, albeit in the Roman style. The statue of Aulus Metellus is but one example of later Etruscan bronze ware.

More about this subject : see our partnerís page

Etruscan mirrors

Etruscan mirrors were generally cast in bronze,which is an alloy of copper and tin. Etruscan bronzes also occasionally contained a smaller proportion of lead, but no zinc. The tin was originally traded with the Gauls, who probably obtained it from the British Isles (Cornwall), but in later years, tin was discovered at Campiglia, near Populonia.

Etruscan mirrors were generally cast in one piece, with a blunt spike known as a tang. This tang was then inserted into a handle made from some other material such as wood, timber, bone or ivory. However in some examples, the mirror was cast entirely in bronze and included an integral bronze handle.

Etruscan mirrors were generally cast in one piece, with a blunt spike known as a tang. This tang was then inserted into a handle made from some other material such as wood, timber, bone or ivory. However in some examples, the mirror was cast entirely in bronze and included an integral bronze handle.

The reverse of many Etruscan mirrors have a picture engraved or moulded in low relief. The front of the mirror was highly polished using such materials as ground pumice or cuttle fish bone. Later mirrors were made with bronze containing a higher proportion of tin. This resulted in a more resilient surface which was brighter in colour and therefore gave a better reflected image.

The image on the reverse of Etruscan mirrors generally showed pictures of Women, often (but not always) in a mythological context. In many cases, Greek mythology is depicted, but often with an Etruscan theme, or altered from the original Greek myth in some way. Examples of such scenes include the birth of Athena (Menerva) from the head of Zeus (Tinia), the labours of Heracles, including some unknown Etruscan variants, and the Dioscuri, usually accompanied by a female figue, (Leda/ Latona ?).

Mirrors deposited in tombs were often deliberated destroyed by scratching "suthina" (pertaining to the Tomb) on the polished surface.

Often text on mirrors was written from right to left, or in both directions, depending on the overall aesthetic effect desired. It is interesting to note that unlike contemporary Greek mirrors, many Etruscan mirrors although designed for women, had numerous inscriptions on them, which supports the other evidence about the high literacy levels (and social standing) of Etruscan women.

More about this subject : see our partnerís page

|

The image left shows part of the antefix from the temple of Juno Sospita, Lanuvium (6th - 5th Century BCE). This terracotta depicts a maenad, Many similar examples have been found, in many cases with traces of the original polychrome decoration. The characteristic smile is shared by many statues of the contemporaneous Greek Archaic period.

Etruscan Art has been said by some 19th and even 20th Century writers to be somehow inferior, although this was usually by erroneous comparison to the Greek mathematical ideals of beauty. Nowadays we can appreciate Etruscan Art much more readily, since Etruscan Artists seem to capture the feeling and the essence of so many of their subjects so much better than for example art of the highly stylised Classical period.

The image left shows part of the antefix from the temple of Juno Sospita, Lanuvium (6th - 5th Century BCE). This terracotta depicts a maenad, Many similar examples have been found, in many cases with traces of the original polychrome decoration. The characteristic smile is shared by many statues of the contemporaneous Greek Archaic period.

Etruscan Art has been said by some 19th and even 20th Century writers to be somehow inferior, although this was usually by erroneous comparison to the Greek mathematical ideals of beauty. Nowadays we can appreciate Etruscan Art much more readily, since Etruscan Artists seem to capture the feeling and the essence of so many of their subjects so much better than for example art of the highly stylised Classical period.

Etruscan gold work was arguably unrivaled in the Mediterranean during the first millennium BCE. A considerable selection of Gold jewellery was found in the Regolini Galassi tomb, which

Etruscan gold work was arguably unrivaled in the Mediterranean during the first millennium BCE. A considerable selection of Gold jewellery was found in the Regolini Galassi tomb, which  was discovered in the 19th Century, surprisingly with little evidence of looting. Looting was all too common in Ancient days, and was even encouraged officially by Alaric the Goth when his armies overran Rome in the early 5th Century AD.

was discovered in the 19th Century, surprisingly with little evidence of looting. Looting was all too common in Ancient days, and was even encouraged officially by Alaric the Goth when his armies overran Rome in the early 5th Century AD.

The sculpture on the right (actually a hollow cinerary urn) comes from the Banditaccia necropolis, Cerveteri, and is known as the Sarcophagus dei Sposi. It is currently exhibited in the Villa Giulia museum in Rome. The terra cotta sarcophagus lid with figures of a man and woman, presumably his wife reclining on a triclinium or dining couch presumably eating a meal or having a quiet moment after supper

The sculpture on the right (actually a hollow cinerary urn) comes from the Banditaccia necropolis, Cerveteri, and is known as the Sarcophagus dei Sposi. It is currently exhibited in the Villa Giulia museum in Rome. The terra cotta sarcophagus lid with figures of a man and woman, presumably his wife reclining on a triclinium or dining couch presumably eating a meal or having a quiet moment after supper  A very similar sarcophagus to this was also found in Cerveteri. They are believed to be by the same artist and date to 520 - 530 B.C.

A very similar sarcophagus to this was also found in Cerveteri. They are believed to be by the same artist and date to 520 - 530 B.C. The production of funerary urns, followed by black pottery gave birth to the Bucchero Nero, which was practiced up to the sixth century BC. The walls, which were initially thick, gradually became thinner, reaching their ultimate quality during the seventh century. Bucchero nero consists of a clay which is tinted black or sometimes gray, using a reduction process similar to metallurgical techniques. After polishing to produce a metallic sheen, it is often decorated with figures that are engraved, modelled in relief or carved. Among the many shapes obtained, the chalice, the high-handled kantharos and the amphora with two handles and bearing incised drawings are particularly typical. They aim to imitate bronze, which is much more expensive.

The production of funerary urns, followed by black pottery gave birth to the Bucchero Nero, which was practiced up to the sixth century BC. The walls, which were initially thick, gradually became thinner, reaching their ultimate quality during the seventh century. Bucchero nero consists of a clay which is tinted black or sometimes gray, using a reduction process similar to metallurgical techniques. After polishing to produce a metallic sheen, it is often decorated with figures that are engraved, modelled in relief or carved. Among the many shapes obtained, the chalice, the high-handled kantharos and the amphora with two handles and bearing incised drawings are particularly typical. They aim to imitate bronze, which is much more expensive.

Throughout the Etruscan period, we also find unglazed funerary or votives ceramics without any paintings, but decorated with engraved figures or figures modelled in relief before the clay had hardened. Their shape sometimes recalled everyday objects such as stoves, ovens and containers. The patterns include human figures, monsters borrowed from eastern Asia, and geometrical drawings. In Chiusi, in Volterra, Vulci, the drawings are rather in relief, whereas they are more often hollow in Veies.

Throughout the Etruscan period, we also find unglazed funerary or votives ceramics without any paintings, but decorated with engraved figures or figures modelled in relief before the clay had hardened. Their shape sometimes recalled everyday objects such as stoves, ovens and containers. The patterns include human figures, monsters borrowed from eastern Asia, and geometrical drawings. In Chiusi, in Volterra, Vulci, the drawings are rather in relief, whereas they are more often hollow in Veies.

a poem by Critias in saying "Etruscan cup of beaten gold is king, and any bronze whatever that adorns the house for any purpose". Again from Athenaeus, a character in a play by Pherecrates is quoted as saying "The lamp stand was Tyrrhenian... for manifold were the crafts among the Etruscans, since they were skilled and loving workmen". Vitruvius in his famous work on Architecture refers to the superlative gilded bronze statues of the Etruscans, and Pliny the Elder writes "There are also Etruscan Statues dispersed in various parts of the world, which beyond any doubt were made in Etruria".

a poem by Critias in saying "Etruscan cup of beaten gold is king, and any bronze whatever that adorns the house for any purpose". Again from Athenaeus, a character in a play by Pherecrates is quoted as saying "The lamp stand was Tyrrhenian... for manifold were the crafts among the Etruscans, since they were skilled and loving workmen". Vitruvius in his famous work on Architecture refers to the superlative gilded bronze statues of the Etruscans, and Pliny the Elder writes "There are also Etruscan Statues dispersed in various parts of the world, which beyond any doubt were made in Etruria".

Etruscan mirrors were generally cast in one piece, with a blunt spike known as a tang. This tang was then inserted into a handle made from some other material such as wood, timber, bone or ivory. However in some examples, the mirror was cast entirely in bronze and included an integral bronze handle.

Etruscan mirrors were generally cast in one piece, with a blunt spike known as a tang. This tang was then inserted into a handle made from some other material such as wood, timber, bone or ivory. However in some examples, the mirror was cast entirely in bronze and included an integral bronze handle.